Sometimes, when accompanying a person affected by tuberculosis (PAT), Marlene Osorio notices when someone has taken their medication and when they have not. It’s not intuition, it’s memory. Almost ten years ago, she herself had the disease and, at some point, also hid one of the many pills she had to take each day.

“Every person with tuberculosis (TB) lives something that I have also lived,” says Osorio. He still remembers that, after recovering, he felt an indefatigable curiosity to better understand what he had gone through. “A lot of things happen to you as an affected person, and that’s when you need other people,” he says.

That’s why she decided to join an Organization of People Affected by Tuberculosis (OAT) to provide support to people with TB who, like her, were looking for support from someone who had experienced the disease firsthand, faced difficulties in accessing health services and overcame the many challenges of care.

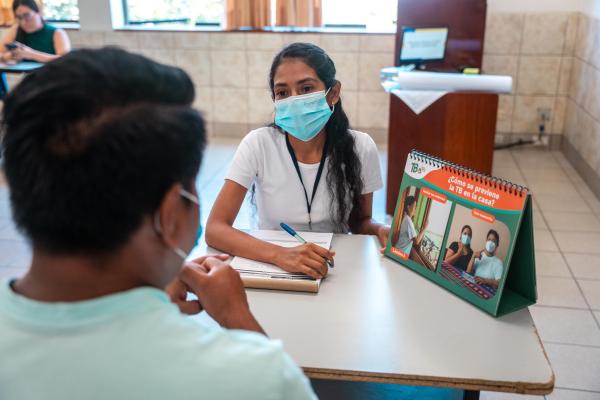

This experience encouraged her, in 2023, to join an intervention aimed at developing a pilot tuberculosis peer counseling scheme. Implemented by Partners In Health in coordination with the Ministry of Health (MINSA - DPCTB) and the National Multisectoral Health Coordinator (CONAMUSA), this initiative is part of the Country Project TB-HIV 2022-2025. As a first step, Osorio completed the TB Peer Counseling Courseto strengthen her skills. Since October 2024, like his fellow promoters, he has been providing counseling sessions at health facilities in northern Lima.

Peer counseling is an accompaniment strategy in which people who have overcome tuberculosis (TB) or are in the last stages of their treatment - known as peer counselors - provide emotional support and guidance to other people affected by the disease. Their role is key in TB prevention, health promotion and control, as they help improve adherence and increase the likelihood of successfully completing therapies.

“In my time, except for my family, I lacked a person to listen to me. My case was terrible, because my treatment was for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) and it lasted almost two years,” says Jessica Palacios, who overcame this disease 15 years ago and today is part of an OAT in the Villa María del Triunfo district southeast of Lima.

Like Osorio, Palacios was one of 34 people invited to the first edition of the course. With a decade of experience as a peer counselor, she assures that training has provided her with valuable tools. “The teaching we have been given has guidelines, methodology and dynamics,” she says. “Helping others is what has motivated me.(To the PATs) I give them a little of my time, I listen to them, we talk, we fill each other with information, we exchange experiences.”

Training to Transform

Tuberculosis continues to be a public health problem in Peru. Despite having effective treatments, their success is affected by the lack of follow-up and the vulnerable conditions of the people affected. In 2020, 4.6 % of TB patients abandoned their therapy, and in 2019, the loss rate in MDR-TB cases reached 18.5 %.

Thus, MINSA incorporated peer counseling in its technical health standard as part of the guidelines for TB prevention and control. This strategy promotes health with a focus on rights, equity and interculturality. “It highlights the importance of accompaniment, education and psychosocial support to strengthen adherence to treatment and prevention,” says Diana Yupanqui, training specialist at Proyecto País.

“When we present ourselves as someone who has gone through the same thing, people are more willing to listen to us, which is different from when they receive instructions from medical staff,” explains Sofía Canchari, a peer counselor who had TB 15 years ago and this year is taking the second version of the TB Peer Counseling Course.

In both editions of the course -the first one in 2023 and the current one in 2025-, a call for applications was made to the TAOs linked to the TB-HIV Country Project. For the selection, criteria were established such as belonging to a TAO, having at least six months of participation in the organization and having been a person affected by TB. In the second edition, qualitative interviews were added to assess the applicants’ knowledge of TB and their responses to simulated cases of TAP in different scenarios, including health facilities and their environment.

“So far, the course has given me a better understanding of the disease, the recovery process and the adverse effects of drugs, something we need to explain clearly to patients,” says Canchari, who is completing this training in a class of 23 PATs from Metropolitan Lima and regions such as Chimbote, Iquitos and Trujillo.

Yupanqui highlights the educational approach of the course: “It integrates reflection and practice as pillars of the training process”. Structured in three units, the program addresses essential topics such as community TB care, theoretical foundations of the disease and peer counseling. This last section includes two face-to-face workshops designed to strengthen communication skills, social-emotional management and simulated practice of counseling sessions.

“Each teacher is unique in the way he or she conducts classes. There are many new things, such as terminologies and medications, several of which I didn’t even take at the time,” says Alberto Amaya, another peer counselor who overcame MDR-TB 18 years ago and is now also taking the course. “I have experience accompanying people with TB, but with this training I will be able to do even better,” he adds.

“When we present ourselves as someone who has gone through the same thing, people are more willing to listen to us,” explains Sofía Canchari, a peer counselor who had TB 15 years ago.

Empowering with knowledge

Marlene Osorio knows that her work is not limited to sharing information. She seeks to connect with each of the people affected with TB that she visits in districts such as Puente Piedra, Independencia and Comas, conveying confidence and clarity in her messages. To do this, he combines theoretical knowledge with practice, adapting to the needs of each patient.

“(To PATs) I explain that they should take care of themselves and protect others. I always give them an example: ‘Have you seen Goku [character from the cartoon Dragon Ball]? When he gets hit, he gets stronger. That’s how bacteria are. If you don’t take the pills, they will become resistant and the medicine won’t work anymore,’” he says.

Osorio and Palacios know that the first 30 days of treatment are key to avoiding dropout, especially in people with drug dependency problems whom they accompany. Each case poses a complex challenge, and added to that is the task of helping them confront stigma with information.

“Before, we didn’t know our rights,” says Palacios, who does counseling in Villa María del Triunfo. “Now health centers are more empathetic. In addition to accompanying PATs, we take talks to markets, parishes and soup kitchens to talk about stigma and discrimination.”

Peer counseling is also empowering. “Thanks to the trainings, I have changed a lot. Before I was very shy, it was hard for me to speak in public. Today it matters little to me that they know I had TB; what is valuable is that the community learns how to prevent the disease. And to the patients I say: don’t be discouraged, this disease can be cured,” says Palacios.

Strengthening the skills of affected people to become community leaders is how Socios En Salud transforms personal experiences into tools for change. With each new class of counselors, the support network grows, demonstrating that recovery is a road that no one must travel alone.

Be part of the change. Get our actions, stories and opportunities to transform lives in your inbox. Subscribe here and join our movement for health!